Homeless & Hiding: Mumbai Street Children During the Lockdown

Where did the most vulnerable children go?

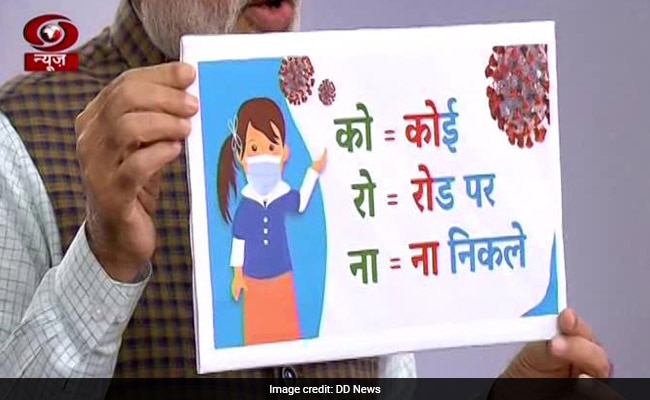

At 8 pm, on 24th March 2020, the Indian Prime Minister appeared on national television holding a poster that extrapolated each syllable of the word co-ro-na to mean ‘koi- road par- na nikale’ (No One Should Go Out on The Roads). If the nation was to overcome the virus, the PM declared that – ‘No matter what, we should stay at home.’

It may that seem that one sentence (no one should be out on roads) leads logically and progressively into the other (we should stay at home). But it fails to take into account is that for many of the 1.7 million homeless Indians, the road is their home.

4 hours after the PM’s announcement, the nation would go into an unprecedented lockdown. 1.7 million Indian who had no roof over their head now didn’t have the ground beneath their feet.

The homeless in India are at the risk of the full crush of the pandemic- medical, financial & social. Instruments of basic hygiene are beyond their means. Their precarious income generation is at a standstill. From all accounts, the only service the state can seem to guarantee is a lathi charge. And all this, without accounting what happens to those who are vulnerable to sexual violence or addicts living through the agony of withdrawal.

The numbers are vague and difficult to determine but one account estimates that 400,000 to 800,000 of this population are children.

Approximately, 37,000 of whom live on the streets of Mumbai.

The On Ground Situation

Post the lockdown, many of the NGO workers working with street children have not been unable to get in touch with these children. On ground outreach has been difficult, if not impossible. And as for mobile phones, this is a population that still mostly exists outside the grid and the lockdown has only pushed them further into the dark.

So where did the street children of Mumbai disappear to?

Navnath Kamble, a senior child rights activist from the Pratham Council for Vulnerable Children says that many of the street children in Mumbai city who are below 14 years of age, and have no families have been placed in institutions before the lockdown. Many of those who have families living in the outskirts of the city have returned to their homes. However street living children, especially the older boys between 16 to 18 years of age who are without families continue to be at risk.

Altaf Shaikh, co-founder of the Urja Trust in Mumbai, says that some of these boys continue to live in the heart of Mumbai. They are no strangers to crackdowns by the state. They hole up in ‘hiding places’ like the underneath of bridges, insides of large godowns and other unsurveilled nooks of the urban sprawl that they have mapped out for refuge.

The boys are aware of places in nearby communities where cooked food is distributed, or hang around markets which are open to pick up the vegetables fallen on the ground which they later manage to cook and eat. Whatever the situation, they always manage access to basic sustenance.

However Altaf says that if one draws a parallel from past experiences during the 1992 Mumbai riots, the street children of Mumbai may have more to fear from societal prejudice & backlash than the lockdown itself.

Street living boys are easy targets and scapegoats for any situation that may crop up in the city. In the event of the community spread of the pandemic, they stand to be ostracized in the resulting blame game. If the economic turmoil of the lockdown results in a surge in crime rates, it will be these boys who will be routinely picked up for petty thefts and subject to questioning and brutality.

Altaf is not surprised that street living children did not feature in the public discourse around the pandemic despite being one of the most marginalized communities in the country who are at the highest risk of being abused, exploited and neglected.

“Even before the pandemic, how much were they a part of public discourse around policy and welfare?”

Addressing the Negative Space

When the existence of around 1.7 million Indians is negated one night in the duration of around 5 minutes over a national telecast, it tells of a crushing marginalization that has been allowed to accumulate for a while.

Without doubt, there has been a massive failure on part of the state and its machinery. But let’s also look closer home at policy discussions within civil society.

There has been a rising trend where majority interventions are designed to be dispensed through the school system. This has been fueled partly by the needs of the system as well as the desire for scale & sustainability. All of which are worthy goals.

Whenever these discourses are conducted there are voices that call for a focus on children who are not in school (including street living children). At this point, there is a sentiment expressed that the need is to prioritize & reach out to children in schools first and only then focus on the out of school children at a later date. And in most cases, the later dates never arrived. Or the pandemic arrived first.

The street children of India have been turned into a negative space in policy discourse whose presence is felt but only sometimes acknowledged and almost always passed over. And it is no surprise that the same was repeated at the highest levels when the lockdown was announced.

These children have always fended for themselves. The least we can do is support them by being adamant, stand with them against any coming backlash and make way for their representation and inclusion in policy & action.

(Help support Homeless families in Mumbai during the pandemic. Click here to donate to our friends at Yuva who have been doing some terrific work.)