4 Years Since POCSO: Unfolding of the POCSO Act in The State of Maharashtra

The Aarambh India Initiative’s research titled ‘4 Years Since POCSO: Unfolding of the POCSO Act in the State of Maharashtra‘, put together by Dr. Pravin Patkar & Pooja Kandula is the first ever of its kind in scope and scale.

The Aarambh India Initiative’s research titled ‘4 Years Since POCSO: Unfolding of the POCSO Act in the State of Maharashtra‘, put together by Dr. Pravin Patkar & Pooja Kandula is the first ever of its kind in scope and scale.

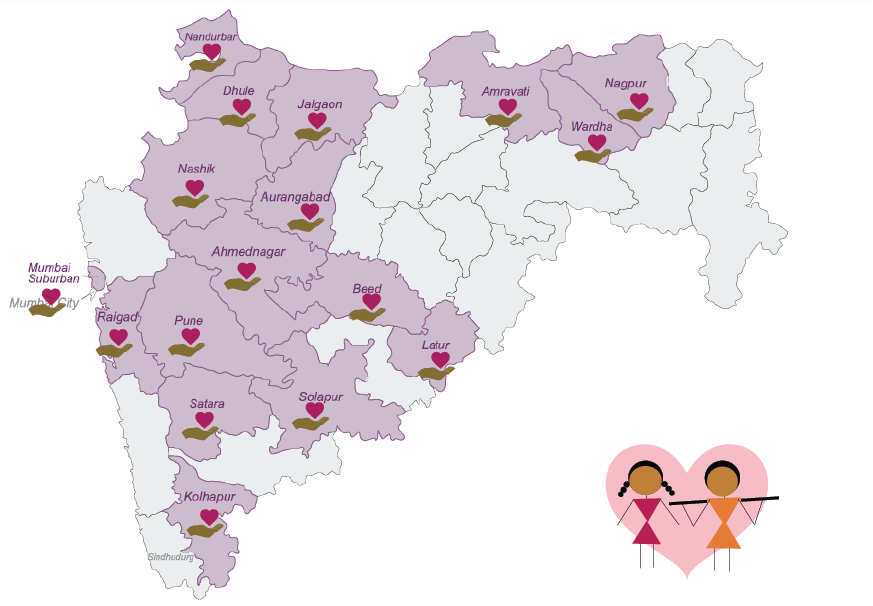

The research takes a critical look at the on ground implementation of India’s Child Protection Law – the POCSO Act. It does this across 7 key stakeholders – Police, Public Prosecutors, Juvenile Justice Boards, Child Welfare Committees, District Child Protection Units, Hospitals & Civil Society Organizations – and 17 districts with diverse socio-economic backgrounds from teeming metropolises (Mumbai, Pune) to small towns (Satara, Dhule) to districts listed as ‘backward’ (Nadurbar, Jalgaon). In all, we reached out to a total of 147 respondents. Many of these voices have worked for years but are being heard for the first time.

The resulting data is varied and rich. It not just offers a striking overview on the state of child protection systems in Maharashtra but more importantly presents the attitudinal landscape of these systems. It shows that child friendliness cannot be measured merely in procedural efficiency but alos in the dignity and sensitivity it offers a child victim of sexual abuse.

The study offers recommendations of how best to bridge these key gaps may be bridged and create robust child protection systems that align to the principles of ‘the best interest of children’.

Find the highlights as well as the full research report below.

Stakeholder-wise Snapshots & Other Highlights:

Please click Through Below for a quick overview of the findings & recommendations of the research.

1. Police

Number of Respondents: 64

POCSO Awareness Score: 56%

Click below for:

- – Findings

- The nuances of the various laws, their overlapping areas and the gaps between them are not clear to most of the police personnel.

- POCSOA considers it to be the responsibility of the police personnel handling cases to ensure child friendly practices such as – not presenting themselves before a victim child in police uniform, arranging for shelter and other needs of the child if found in need of care and protection, protecting the identity of the child, not letting the accused and his representatives encounter the victim child, reporting the matter to the CWC, mobilizing the other service providers, and to follow a distinct timeline. The comprehensive understanding of child friendly practices was not reflected in the responses given.

- All (64) police respondents stated that theoretically they understood the age of the child as 18 years old, however in every interaction they mentioned that they only view any person below the age of 12 years as a minor. They also mentioned that they felt that cases of children below 12 are always genuine. They admitted that child friendly practices are unhesitatingly followed when the child is below 12 years of age.

- In a vast majority of police stations there are no women PSIs. There was a stark difference noted in the availability of lady PSIs in urban and rural areas. In urban areas, every police station had at least 1 lady PSI dedicated to working on cases of children. In rural areas it was not uncommon to find only 1 lady PSI for 15 or even 25 police stations.

- Between 2 pm to 5 pm there was not a single police officer (of the levels of PSI & PI) present in 20 police stations that were visited.

- Majority of the police stations had no separate rooms or waiting areas that could provide privacy to the victim or the family. 64% of rural police stations had no separate waiting rooms. Majority of the rural police stations lacked functional toilets.

- In most districts, when a case comes to their attention, the police take the victim child in a bus or a private vehicle to the district head-quarters. In some cases families are asked to reach the district headquarters on their own. Thus the family has to spend a considerable amount of money every time they are called to the court. Sometimes the accused and the victim are taken in the same vehicle to the district headquarters.

- Only one police officer is trained in POCSOA from each police station. When this police officer is on leave or transferred, other officers are assigned to handle the cases without having the necessary orientation to do so. This, by the police personnel’s own admittance, is problematic

- Several officers mentioned the use of a software application named Hashdroid while recording the evidence of the child using an audio-visual medium. Hashdroid assigns a unique ID (i.e hash) to the digital file of the recording. This helps prevent any form of tampering with video evidence. Some of these videos have been accepted in the court as evidence.

- Many police stations mentioned not taking down complaints which do not fall in their jurisdiction although POCSOA states otherwise. However, all police respondents also admitted that they had to mandatorily record every complaint under POCSOA that comes to their police station. This is a paradox.

- Despite the fact that the law does not make it mandatory, all the police respondents (100%) mentioned that recording of a statement of the child under Sec 164 of CrPC as among the most important 5 steps they would follow on receiving a POCSOA complaint.

- The understanding of the police personnel on the need for medical examination in cases of child victims of offences under POCSO Act is at variance with what is mandated under POCSOA.

- More than half of the police respondents (61%) stated that not every child against whom an offence under POCSOA has been allegedly committed is sent for medical examination. 39% police respondents mentioned that they send only the cases of ‘rape’ falling under IPC Sec 375/376 for medical examination. This is a serious misunderstanding.

- The prime and exhaustive purpose of conducting a medical examination for POCSOA cases is not clear to most of the police personnel working on the frontline.

- Less than half (39%) police respondents mentioned that they have to report every case of POCSOA to the CWC and another 17% mentioned they have to report every case to a court.

- Although the majority of the police respondents stated that they had no challenges in working with CWC, 38% of the police respondents also stated that they had no interaction with the CWCs on the POCSOA cases that they handled.

- As regards the adequacy of the services for children in their district 78% said service were adequate while 22% said they were deficit.

- 83% police respondents were aware of the Manodhairya scheme and 78% were aware of their role under it.

- As many as 61 % of the responses stated that the child’s statement is taken at the police station which is against the spirit of POCSOA. Of these, 2 police personnel specially mentioned that they record the statement in camera in a private room inside the police station.

- The presence of a women police officer and the care to be taken not to present oneself before a child in police uniform seem to have been noted and registered by most of the police respondents as the key child friendly practices to be followed under POCSOA.

- 45% police respondents stated that they had not come across cases of differently abled child victims of POCSOA offences. This indicates a worrying possibility that incidences of sexual abuse against differently abled children may still be going unreported.

- Only 20 police personnel mentioned that a statement of the victim child by itself is evidence, in line with the new addition brought about by the POCSOA.

- A majority (66%) of the police personnel feel that the provision for mandatory reporting should be kept. However, there is also an indication that the provision is not taken up seriously by the police and the state and is not being enforced in text and spirit.

- – Recommendations

- The current level of awareness of the police as the frontline duty bearers about their role and responsibilities, the salient provisions of the POCSOA, and its interfaces with the other important laws is far from satisfactory. This needs to be improved through formally accredited capacity building programmes.

- The police needs to be sensitized, trained and supervised to ensure that it adopts child friendly practices while dealing with children under POCSOA. This must apply to all persons below 18 years of age regardless of the police personnel’s individual biases and preferences.

- Most social legislation requires sensitive handling of women and children at all levels including the police stations. This in turn requires the presence of a trained woman police officer. It is recommended that every police station must have at least one woman PSI. The current discrepancy between urban and rural police stations with respect to the presence of woman PSI is serious and needs to be corrected.

- All police stations should be equipped with a spare room which can be used as a separate room for the victim and her/his legal guardians and support persons in order to ensure their privacy to them. The police stations must observe certain minimum standards in terms of infrastructure, super structure and amenities like toilets, washrooms, eating areas etc.

- It is necessary to transport the accused and the victims in separate vehicles in order to ensure sight and sound separation between them. However it is noted that practical considerations may make it difficult to keep a special vehicle for the same. Notwithstanding that, the above separation can be ensured by temporarily hiring a separate vehicle for this purpose. The transportation facility must also be offered to the parents/ legal guardians of the child victim especially in rural areas especially if they are required to report to the district headquarters.

- The police officer/ personnel who are deputed for the external sensitisation & training or capacity building programmes should have the responsibility to train a couple of other personnel from their police station. They can then work as short term substitutes in situations where the trained officer is on leave.

- Registration of FIR under POCSOA should not be left at the discretion of the staff and officers at the police station alone considering the age old reluctance of the police stations to register an FIR. The police superior should closely supervise if the IO is taking all the required / essential steps required under the law and the rules when a complaint under POCSOA is made. The use of net based digital technology for monitoring is highly recommended.

- All police stations must be well equipped to handle the computer hardware and software and internet based solutions to the extent required of them.

- In terms of the handling of the POCSOA cases at the police station level, several factors can cause a great variance including the level of understanding of the field level police personnel about POCSOA, their roles and responsibilities under POCSOA, and the scope for them to interpret the provisions and to use their discretion. Often a medical examination under POCSOA is understood in a limited manner as mere physical examination to ascertain sexual penetration or to record physical injuries if any. Hence where there is no complaint about penetrative sexual offence the police tend to use their discretion and conclude that a medical examination is not necessary. As the first corrective step the police should not be given the authority to use this discretion. Secondly, in light of the fact that considerable injury is caused to the victim that is psychological in nature, mere physical examination cannot bring it on record. The law or the Rules of POCSOA may be suitably changed to make provision for a mandatory psychiatric assessment of the impact of the offence on the victim.

- The near absence of registration of complaints of sexual offences against the differently abled children points towards a grave situation of complete silence and non-disclosure of offences on this front.

- The police and other frontline duty bearers who come across POCSOA victims must be made aware of their responsibilities under the POCSOA. As of now, there is a differential interpretation of their roles under POCSOA.

2. Public Prosecutors

Number of Respondents: 18

POCSO Awareness Score: 48%

Click below for:

- – Findings

- A large majority (83%) of prosecutors had dealt with cases of sexual offences against children prior to POCSOA.

- Notwithstanding the fact that POCSOA mentions the age of the child as 18, in the understanding of the prosecutors, child friendly procedures are being adopted in most districts courts only when the child is 12 years or below.

- Although a large majority (83%) of public prosecutors mentioned that they have designated court rooms for POCSOA, the courts are not exclusively dedicated to POCSOA cases. They also try other cases in which adult women are involved.

- With negligible exception, all the special courts in these districts do not have a separate waiting room for the victim. The victim is made to wait either in the public prosecutor’s office or outside the court room risking exposure to and contact with the accused and/or his representatives.

- Most district courts (71%) had cameras and curtains/ screens to separate the victim and the accused. However, not all courtrooms in a court that are used as special POCSOA courts are thus equipped.

- The above fact compounded by the appalling lack of child friendly infrastructure and facilities indicate a worryingly casual approach to the issue of confidentiality and dignity of the child.

- Almost half of the special courts (53%) did not have a special public prosecutor for POCSOA cases.

- Half (50%) of the prosecutors observed that POCSOA special courts have expedited the disposal of cases.

- There is lack of understanding and clarity with respect to certain procedures laid down by POCSO to protect the identity of the victim and follow child friendly practices. Some examples cited by the respondents included:

a. The defense counsel remains present while the statement of the child is recorded under CrPC 164.

b. Interaction between the accused or his/her representatives and the victim is allowed.

c. Direct questioning of the child by the defense counsel is allowed. - The prosecutors blame the delay by the police and doctors in submitting their reports as the major reasons for delayed disposal of cases.

- Prosecutors have difficulties in understanding the language of the victim child when they are extremely young of age.

- Majority of prosecutors are in favour of keeping the provision of mandatory reporting intact.

- – Recommendations

- The State should undertake accredited sensitisation and training of the Public Prosecutors handling the POCSOA cases.

- The State should urgently provide at least the minimally required infrastructure, basic amenities and facilities under POCSOA at the District courts. The current state of affairs indicates gross violation of the text and spirit of the POCSOA.

- The appointment of special public prosecutors should be made on priority basis.

- Like the other stakeholders and duty bearers, child friendliness of the procedures under POCSOA is little understood by the prosecutors. The spirit and the substance of child friendliness procedures and practices should be elaborately codified and mainstreamed through protocols, SOPs, manuals, checklists, training programmes and online courses for prosecutors.

3. Juvenile Justice Boards

Number of Respondents: 7

POCSO Awareness Score: NA

Click below for:

- – Findings

- All of the JJBs had full time women Magistrates appointed to them. The JJBs were located in the premises of the Observation Homes (OHs) where one room was allocated to the JJB. However, there are no separate rooms for the purpose of waiting and counseling of the victims of POCSOA cases.

- The JJBs had support staff for registering and digitalizing the cases.

- No JJB mentioned coming across any accused child under POCSOA below 12 years of age.

- Most JJBs thought that the increase in the number of cases of sexual offences against children is due to sexual curiosity & experimentation among teenagers which has been fueled by exposure to media and internet.

- All the JJBs mentioned that they conduct a social investigation report for every child that enhances their overall understanding about the child and helps them make decisions in the best interest of the child. One of the factors responsible for this consciousness could be the Order given by the Mumbai High Court in Prerana Vs. State of Maharashtra case (Criminal Writ Petition No 1694 OF 2003).

- All JJBs are aware that the child victim must not appear in court multiple times and efforts need to be made in this direction. This indicates a good practice but may also indicate a possible lack of clarity about the POCSOA as the magistrate is talking about a victim child while JJB is also supposed to give child friendly treatment to the child produced before them as a child in conflict with law.

- All JJBs mentioned that the identification parade, an essential part of investigation of the crime is carried out in the premises of the Observation Home itself. This helps reduce the stress of physical transportation of the accused child. However it still raises the question whether such exposure of the victim child to the accused should be avoided or not.

- All of the JJBs agreed that they grant bail to the accused child even when the offence is prima facie established. They all confirmed that bail is given in all cases except when it is felt that it is not safe for the child to go back to. Bails are granted within 24 hours.

- The JJBs mentioned that more creative orders like open community service can be issued in case of a child found in conflict with POCSOA but there is a serious shortage of human resources to monitor such placements. There is a mismatch between the need and the provisions especially in the JJ mechanisms.

- The JJBs pointed out serious shortage of financial resources.

- All the JJBs agreed that their districts had sufficient infrastructure in terms of OHs but they all lacked the minimum quality of services and human resources. This adversely affects the rehabilitation of the child. They lamented that educational and vocational training services were found to be seriously lacking in their districts.

- All of the JJBs felt that the services given in the OH need quality up-gradation. In some districts there is no Observation Home for girls and such girls are sent to the OHs of the neighbouring district. There is a need for proper legal provisions in the law for the rehabilitation of the accused child.

- – Recommendations

- It may be a good practice to have an even allocation of male and femal istrates on the JJB instead of appointing only women magistrates.

- The needs and rights of the juvenile found in conflict with POCSOA should not get neglected while strengthening the mechanisms under POCSOA. The POCSOA offender if juvenile must get rightful treatment as per the JJ Act.

- Better provisions should be made for sight and sound separation between the victim child and the accused and his represenves.

- The provisions in the Observation Homes should follow minimum standards of quantity and quality

OH services for girls should be made available in every district - The law should make proper legal provisions for the rehabilitation of the accused child.

4. Child Welfare Committees

Number of Respondents: 16

POCSO Awareness Score: 43%

Click below for:

- – Findings

- A large majority (75%) of CWCs did not have the full strength of 5 members. There was rampant absenteeism. In many places, barely two members were managing the affairs of the CWC.

- The provision of an odd number of 5 in the composition of the CWCs was made to facilitate a majority decision when there is difference of opinion within the CWC. In one district, it was observed that mostly two members attended the sitting and almost always, they had a difference of opinion between them. Two CWCs did not have a Chairperson. The deficit composition of the CWCs becomes all the more serious as POCSOA has definitely added to the workload and responsibilities of the CWCs. The absence of the full number of members appointed on the CWCs and the routine operation of the CWCs with deficit number of members also raises a serious question about the legal validity of their Orders and decisions.

- It was a good practice that all CWCs had a board outside their offices displaying the details of the CWC members along with their phone numbers and the days, time of the sittings. However a large majority (88%) of CWCs did not start without a delay of an hour or two. The absence of seating arrangements for the children, their parents and other stakeholders causes considerable inconvenience to them as they wait for the CWCs to start their work.

- The absence of separate room for victim children in most CWCs (77%) causes serious violation of the privacy of the child.

- In districts where the CWCs, Juvenile Justice Boards (JJBs) and District Child Protection Units (DCPUs) were located in a common premise, they exhibited better coordination amongst themselves.

- Almost all CWCs (94%) claimed to have obtained some training on POCSOA but half (50%) of them admitted that the trainings did not equip them to handle POCSOA cases.

- Just a third (31%) of the CWCs mentioned that the police report every case of SOAC to the CWC in the stipulated time. 44% of the CWCs complained that the police do not appear before the CWC in spite of having been summoned.

- A majority (69%) of CWCs are under the impression that every child victim under POCSOA must be ‘produced’ before them. They complain that in most districts the police do not actually ‘produce’ every single child victim before the CWC.

- Almost all CWCs (94%) complained that the additional responsibilities placed upon them under the POCSOA are not matched by any administrative provisions or budgets to the CWC.

- Almost all (94%) CWCs were found unaware of the provision of appointing a Support person as per the POCSOA Rules. This is a key provision. Most CWCs seem not to have used that provision at all.

- The CWCs mention that they have access to shelter facilities as well as legal and medical services for child victims of sexual offences in their districts. However their access to counsellors, interpreters, translators and special educators was poor.

- There is a serious lack of connection and mutual awareness let alone collaboration and multi stakeholder team approach between the CWCs and the various stakeholders. Such a situation is bound to affect the child victim of SOAC under POCSOA.

- – Recommendations

- The CWCs should be revamped in terms of their constitution ensuring that the appointments are made in time and no position on the CWC is kept vacant for more than 45 days.

- The performance of the CWC members should be closely monitored in terms of their attendance, participation in training programmes, and participation in the functioning of the CWC.

- The important provision of Support Person has been largely left unused by the CWCs. It is recommended that CHILDLINE which is a national programme of the government may be appointed to function as the Support Person where other willing and competent persons or bodies are not available.

- On its part the CWCs on their own must prepare a list of organizations that can be appointed as Support Organizations.

- Under the POCSOA Rules, the CWC has to issue the Order appointing a Support Person. The CWCs should be made aware of this provision in the Rules. The CWCs should be made aware that the work of the organizations in helping the victim child in the court gets considerably boosted if the CSO possesses the above Order and produces it in the court. The CWC should know that the police too are mandated to inform the Court about the appointment of the Support Person. The CWCs should make the maximum use of this valuable provision in POCSOA Rules.

- The JJA Rules should be amended suitably or elaborated in order to bring more clarity on the validity of decisions and Orders passed by the CWC when the attendance of the members is in deficit.

- The training programmes for CWCs should have higher accountability.

- The CWCs need to be provided with a comprehensive and accredited training on POCSOA and on its interface with the JJA.

- The CWCs should be put in touch with the various service providers whose expertise and goodwill can be harnessed in the handling of POCSOA cases for better child protection.

- There is an urgent need to ensure that the CWCs routinely work in collaboration with the other stake-holders.

5. District Child Protection Units

Number of Respondents: 14

POCSO Awareness Score: 34%

Click below for:

- – Findings

- All the DCPUs across the districts were understaffed. Not a single DCPU had a full team of 13 members as prescribed under the ICPS.

- The lack of adequate human resources in the DCPUs posed severe challenges to their overall functioning. They seemed unable to devote sufficient time to comprehensively carry out their myriad responsibilities viz a viz numerous departments, schemes & laws.

- Given the vast geographical area of each district, it becomes a challenge for a single DCPU to cover there are of jurisdiction.

- The appointment of the DCPU staff is contractual and the staff salaries are not released on time. Thus most of the members of the DCPUs mentioned being highly demotivated.

- The offices of the DCPUs in 5 districts were in the same premises as that of the CWCs and the JJBs. In such scenarios it has been observed that these three systems work very well together. On the other hand, the DCPUs in majority of the districts (8) were in the same premises as the DWCD office. In such scenarios, there seemed to be a lack of autonomy among the DCPUs who claimed to be burdened by the DWCD with tasks other than their mandate.

- Wherever the DCPUs claim to have managed to establish good rapport and linkages with the other stakeholders, the cases under POCSOA appeared to have been handled relatively well.

- There is no awareness among other stakeholders especially medical professionals, police, and the Courts about the existence of the DCPUs. Only 68% of respondents interviewed were aware of their existence.

- A majority (57%) of the DCPUs do not get informed about the POCSOA cases registered in their districts.

- The availability of resource directories with the DCPUs is patchy at best. Even those DCPUs who have the lists have not yet disseminated them among other stakeholders citing the lack of funds for printing.

- Many DCPUs complained that they have limited budgetary discretion and that every decision they make needs to be cleared in advance by the state level ICPS. None of the DCPUs paid for any services rendered by the experts while handling the POCSOA cases.

- Half of the DCPUs (50%) provided counseling services. Almost a quarter had appointed counselors whose services were not being used. The remaining did not have counselors.

- It is shocking to note that not a single DCPU under the Study was aware of the provisions where they could be appointed as a Support Person under POCSO Rules.

- An overwhelming majority of DCPUs (86%) claimed that they conducted Home Investigation, submitted Home Investigation Reports and followed up with the victims’ families to ensure that the victims get criminal injuries compensation.

- Majority DCPUs (71%) claimed to have organized trainings on JJA and POCSOA for the various stakeholders in their districts.

- Majority DCPUs stated that the police take their help in understanding the POCSOA. Surprisingly however, the police in their interviews have said that they did not know of the existence of the DCPUs in their district.

- A dominant majority of DCPUs (71%) replied that special initiatives were being taken in their district to create child friendly environment. These ranged from creation of child friendly CWCs to setting up VCPCs in communities & children’s committees in Shelter homes to create broader awareness about the law and for creating systems of co-ordination among the stakeholders.

- – Recommendations

- The grimly low awareness score of the DCPUs about their own role and responsibilities under POCSOA and that of the other duty bearers is a cause for concern. This must be corrected by orienting them properly, facilitating team work and implementing accountability mechanisms.

- The DCPU despite being key coordination mechanisms for child protection, and hence for JJA as well as POCSOA, is a highly under-provided and ill-equipped agency. It needs optimum provisioning in terms of staff, infrastructure, and other resources as that could directly contribute to the better functioning of several other mechanisms meant for child protection.

- The roles and responsibilities of DCPUs as currently mentioned are numerous but mismatched not just by the lack of provisions but also by lack of clarity about it. This situation needs to be corrected and the DCPUs should be encouraged to focus on their role as coordinators and facilitators of various other key inputs for the systems working under the POCSOA and the JJA.

- The existence and roles of the DCPUs must be made known to the other stakeholders under the JJA and the POCSOA in the district for their optimum utilization.

- The evident gulf between the POCSOA mechanisms and DCPUs needs to be bridged urgently.

- The DCPUs should provide resource directories and lists of service providers to the various stakeholders under POCSOA. This has to be matched by budgetary provisions and/or a mechanism for digital dissemination of the resource directories.

- The lack of knowledge about the key provisions of the POCSOA among the DCPUs especially about the provision to appoint Support Persons or Support Organizations and the gap among the various duty bearers under the POCSOA should be corrected.

- Although the DCPUs claim to have conducted many training programmes the situation does not show any significantly positive impact of the trainings. It is necessary to upgrade the training activity and make it accountable.

6. Hospitals

Number of Respondents: 14

POCSO Awareness Score: 43%

Click below for:

- – Findings

- There was no clarity and uniformity at the level of the hospitals as regards the legally binding procedures of medical examination, consent for medical examination and child friendly procedures etc. Even on the issues of procedures of medical examination of child victims of sexual offences under POCSOA such as age of consent for medical examination, reporting format, examining doctor, forensic kits & tools etc. there is a wide variance and a serious lack of uniformity across the districts.

- There was a gross lack of sensitivity in hospitals as regards the dignity and privacy of the female child victim as witnessed in the field observations gathered by the research team.

- Mostly cases of penetrative sexual assault under POCSOA and Rape (Sec. 376 IPC) are brought to the hospitals for medical examination and treatment. Only in a minority of cases, victims of all kinds of sexual offences under POCSOA (touch & non-touch offences) are brought to the hospital.

- Due to the lack of infrastructural facilities and lady doctors at the PHC levels all child victims under POCSOA are brought to the district level hospitals for medical examination. Their families are often told by the police to report to the district hospital on their own. This causes considerable inconvenience to the victim and his family and may also be resulting in loss of critical evidence.

- The hospitals attribute the delay in medical examination of the child victims of POCSOA to excessive workload. It was not a part of this Study to verify this claim.

- The absence of convergence among the various departments within the hospitals appears to be a common problem affecting the functioning of the duty bearers under POCSOA.

- Mostly the child victims of sexual offences are brought to the Casualty department. They are also taken to the Gynecology and Pediatric departments as well.

- Unlike what is stated under the CrPC and (therefore also in the POCSOA) the hospitals think that the specialists like the gynecologists and forensic experts of the hospital are supposed to conduct the medical examination of a child victim of sexual offences.

- Notwithstanding the wide variation in the doctors’ understanding about the age of consent for medical examination, they all are in agreement that parental consent is necessary if the child to be examined is below 10 years. The confusion is about the cut-off age and not about the need for the consent.

- As the DNA and Forensic labs are located only in some of the metropolises like Mumbai, samples under POCSOA from across the state are sent there causing serious delay in receiving reports, leading to delay in filing the charge sheet.

- Mostly, the police department influences the medical examination by asking for specific findings. Over and above there is no uniformity in the memos submitted by the police of different districts causing large variation in the medical reports.

- The much criticized and recently banned ‘two fingers test’ is still conducted on female children victims of sexual offences. All of the hospitals justified it on the grounds of the need to ascertain vaginal injuries.

- 69% hospitals state that it is important to mention the elasticity of the vagina or the hymen status to make an effective medical examination report.

- As feared by some quarters the provision of mandatory reporting is proving counterproductive in some ways. It may in turn be pushing the crime under the carpet.

- There is a serious absence of networking between the hospitals and the other mechanisms under POCSOA. It needs to be corrected forthwith.

- – Recommendations

- The Hospitals must be held responsible for the violation of privacy and dignity of the child victims.

- Medical examination facilities must be made available at the PHC levels.

- The reasons for the delays in medical examination at the hospital should be probed.

- The procedures at the hospital level must be streamlined and dis-junctures among them should be ironed out. The State should bring in uniformity across the district hospitals in the state on issues like the age of consent for examination, reporting format, examining doctor, forensic kits & tools etc.

7. Civil Society Organizations

Number of Respondents: 14

POCSO Awareness Score: NA

Click below for:

- – Findings

- Rule 4 (Sec 7) of POCSO (The ‘Support Person/Organization’ provisions) operates on a fallacy that CSOs/NGOs like the State are omnipresent and omni-willing to carry out every kind of work on every kind of issue.

- Almost all CSOs (93%) under the Study had handled the cases of sexual offences against children.

- All CSOs mentioned that they report all the cases of sexual offences to the police. However, a vast majority of the CSOs mentioned that they have reported the cases of sexual offences against a child to the nearby CWCs even before informing the local police about it. This is perhaps indicative of their familiarity with the CWC.

- Except for the CSOs that were associated with the CHILDLINE no other CSO had a written protocol for handling the cases of sexual offences against children.

- All CSOs faced challenges ranging from the procedural (delays in filing FIRs, taking multiple statements of the child) to general and socio-cultural (social stigma & taboo around the issue) and the lack of support services like shelter homes, counselling services etc.

- All CSOs mentioned that they did not receive any official order from the CWC to function as Support person. Even as they provided support to the victim and family on their own they were not formally appointed as Support person. This indicates a colossal wastage of a crucially important provision under the POCSOA Rules.

- Majority of the CSOs (64%) mentioned that they play an important role in the pre-trial and trial phases.

- All CSOs appreciated the need for mandatory reporting but not without emphasizing the need for further qualifying mandatory reporting unlike the current sweeping provision.

- All CSOs pointed out that there were no special initiatives that they knew off in their districts for helping the child victims of sexual offences.

- – Recommendations

- While making laws, policies, and programmes the law makers and public administrators should not presume that; the CSOs are present in all parts of the country, CSOs all over the country have uniform background, resource base, mandate, objectives and areas of work, all CSOS are eligible and willing to carry out the work assigned to them by the State or under the law at all times.

- As many CSOs seem to have handled the cases of sexual offences against children they may constitute an important asset and maximum effort should be made to tap their expertise and good will wherever available and possible.

- The CSOs have a relatively better understanding of the rule of law and best interest of child and their good practice of involving the juvenile justice system should be tapped as an asset and used for better implementation of the POCSOA in every way possible.

- The provision of Support Person is extremely crucial. It is unfortunate that it is not made in the text of the law but forms a part of the rules. Further, this provision is not being used by the CWC even when fit support persons or organizations are available in their area of jurisdiction. The dismal state is further compounded by the fact that CSOs are already involved in helping the child victim and are yet not appointed as the Support person in the respective case. This appears unreasonable. It may also be possible that many of these CSOs may not even expect any payments for their services as Support persons.

- Considering the fact that; the CSOs have a spirit of voluntariness as well as a diverse and non-static nature, they are varied with respect to their understanding and style of working. Capacity building efforts should be made and useful protocols and SOPs should be evolved for their better integration in the implementation of POCSOA intensive.

- The intervention and functioning of the CSOs working on POCSOA for better child protection should be facilitated in every aspect.

i. Observations on POCSO Act Trainings

- – Findings

- Although the respondents like Police, CWCs, JJBs have undergone some training on POCSOA mostly they admitted that the training was not sufficient and did not equip them to handle the POCSOA cases in the field.

- None of the training programmes had to follow a curriculum accredited by a body of experts or the State.

- The duration of the training programmes was not suggested or approved by any accreditation authority. It randomly varied from a session of 1 hour to two substantial days.

- No minimum standards were to be followed in terms of the expertise of the resource persons. The resource persons ranged from a fresh graduates working in a CSO with one year experience in working on human trafficking to a police officer or social worker with more than five years’ experience in any field.

- Sometimes very resourceful persons from different fields like social work, law, CSO sector, medicine, are engaged as speakers whose sessions become very educative. Often they are given a session of an hour as part of a poorly designed and administered programme. As the overall design of the training programme lacks professionalism and accountability in spite of involving such speakers, the training programme fails to make the needed impact.

- No minimum standards were followed w.r.t to the training and communication methods used.

- There is an overall rigidity in deciding the trainee group. The training is almost always arranged as per the category of duty bearers. There is a clear lack of understanding about the provisions in the POCSOA and the function of the various other duty bearers created under POCSOA. A better convergence and victim assistance may be attempted in the first instance by having joint training and sensitization across multi stakeholder and duty bearer groups and not separate for each individual category. This will create a better understanding about the presence, roles and responsibilities of the other stake holders and duty bearers with regards to POCSOA.

- Neither the State nor the CSO sector organizations undertaking the training had evolved a standard set of background material or case material as take away for the trainees.

- There was no standard or uniform pre training and post training evaluation to assess the immediate impact of training.

- The trainings on POCSOA was understood as primarily giving out the provisions of the important part of the text of POCSOA piece by piece. The trainings did not cover the broader topics like child sexual maltreatment, child trafficking, violence against children, child protection, gender violence, etc. which are intimately connected with the issue central to POCSOA.

- The trainings did not use case materials that could have helped the trainees apply their learning to concrete situations.

- The curriculum content of trainings lacked research based empirically verified knowledge. More often than not some striking and sensational statistics from a single research study the Government of India’s 2007 study Child Abuse in India were uncritically cited.

- There is no follow up or continuity of the training programmes. Some duty bearers who while attending a training programme take initiative in taking up the contact details of the individual trainers also contact them subsequently when they are confronted with any complicated case.

- – Recommendation

- Pre-service and In-service training should be given the importance that is due to it.

- The State should not interfere excessively in the training or strictly impose a certain curriculum and format on the state and the non-state entities undertaking training on the subject.

- Ideally the State should, in collaboration with the CSO sector and other experts, evolve and disseminate minimum standards for the training content, methods and resource persons to the state and non-state agencies who are interested in undertaking training on POCSOA and other related issues or are entrusted with the responsibility. These minimum standards should equip the trainers and training bodies with background information, situation analysis, case materials, pre-test and post-test evaluation formats, minimum duration, communication technology, use of audio visuals etc.

- The important duty bearers like the personnel of SJPU, members of CWC & JJB, Superintendents of JJ institutions, hostel wardens, recognized service providers must be made to appear for an online test on POCSO – the Act, the Rules and the broader issues of child protection. Effective incentives and disincentives should be attached to their performance in the proposed test.

- Training should be given to multi-duty bearer teams rather than to isolated categories of duty bearers.

- The training should give emphasis on using carefully chosen case material which can encourage the trainees to apply various legal and programmatic provisions to the individual case.

- POCSOA, child sexual maltreatment and the above mentioned topics which are related to it should be incorporated in the syllabi and training contents for professional training of social workers, teachers, police, judicial officers, CWC/JJB members, hostel wardens, etc.

- The state and non-state entities undertaking training should instill accountability in training.

- The State should create a pool of experts who function as trainers who can be made available to the duty bearers in the field for occasional consultation and guidance when in need.

ii. General Recommendations to the State

- – Recommendations

- The Health Department, the Home Department, and the Department of WCD must act in convergence to bring in uniformity in procedures and understanding while dealing with victims and families under POCSOA.

- Currently the prevalent common practice is of taking the statement of the child at the police station. Sec. 24 of POCSOA clearly states that the statement of the victim child can be recorded at the residence of the child or at a place where he usually resides or at a place of his choice. Although the POCSOA does not categorically state that the child’s statement should not be recorded at the police station, it does imply that. As a police station is less likely to be a place of a child’s choice. It is recommended that the state should formally convey that the victim child’s statement should not be recorded at the police station.

- While the CWCs believe and expect that the police should produce every case under POCSOA before them, the text of the POCSOA and Rules do not state so. A substantial section of the police has stated that it has not interacted with the CWC. There appears to be a situation of gap and misinterpretation between these two agencies. The State should clarify to both these agencies the position of the law on this point and the various interfaces as per the law.

- The State must release clear guidelines on medical examination of victims under POCSOA which will comprehensively clarify the steps to be taken and conditions to be met while conducting a medical examination. The following factors need clarity;a. The age of consent for medical examination

b. The indispensability of consent and particularly of a child victim and of a child accused.

c. The propriety of the compulsory presence of a woman representative nominated by the medical institution while conducting medical examination of a male victim especially between 12 to 18 years of age - The confusion between the legality of the established practice of a medical examination of a woman (or female child) by any registered medical practitioner (male or female) in case a woman doctor is not available and the condition in the text of the law Sec 27(2) stating ‘in case a victim is a girl child, the medical examination shall be conducted by a woman doctor’ needs to be removed.

- The State should make the DNA and forensic lab testing facilities easily and promptly accessible.

- There is a clear lack of understanding about the provisions in the POCSOA and the function of the various other duty bearers created under POCSOA. 7. A better convergence and victim assistance may be attempted in the first instance by having joint training and sensitisation across multi stakeholder and duty bearer groups and not separate for each individual category. This will create a better understanding about the presence, roles and responsibilities of the other stake holders and duty bearers with regards to POCSOA.

- The spirit and the substance of child friendliness in procedures and practices should be elaborately codified and mainstreamed through protocols, SOPs, manuals, checklists, training programmes and online courses.

- At the district level there is an urgent need to create collaborative multi-stakeholder structures which make it compulsory to handle the task under POCSOA in coordination with one another.

- The relevant rulings given by various courts should be integrated into the POCSOA training content for the duty bearers.

- There is a need to start child protection initiatives in most districts in partnership with CSOs and existing Government stakeholders.

- Although most stakeholders in the Study opined that the age of consent may be retained at 18 years, there is a need to qualify the provision and not go with a flat cut off age. The age group of 16 to 18 years needs special scholarly examination and special provisions rather than criminalizing it.

- In absence of any other corroborating responses like the actual registering of any cases of non-reporting, the suggestion of many respondents that ‘the provision of mandatory reporting should be retained in the law’ appears like a casual and uninformed response.

- The provision of mandatory reporting in POCSOA is a highly controversial provision and various stakeholders hold diverse opinion on it. The provision should not be enforced strictly without any regards to its real and feared counterproductive effects. Similarly, repealing it outright would amount to throwing the baby with the bath water. There is an urgent need to study this provision more scientifically, exhaustively, comparatively and empirically and to learn from the experiences of the other nations who have been enforcing it for some years.

- The families of the victim child do not disclose teenage pregnancies with the fear of getting dragged in police case inescapably. When they encounter that possibility they walk out and discontinue being in touch with the hospital. As a result the hospitals have stopped reporting such cases under the pressure from the parents. This situation should be addressed by modifying the provision of mandatory reporting. The provision of mandatory reporting must be immediately revised and made useful by eliminating its negative potentialities.

Click here to Download the Findings & Recommendations

निष्कर्ष आणि शिफारशी डाउनलोड करण्यासाठी येथे क्लिक करा

Full Research Report:

Click here to download the full research report including detailed charts, observations, suggestions & recommendations